Orwell’s shooting of an elephant serves as a metaphor for British colonialism in Burma. Although Orwell feels that many Burmese view him with disdain, he still must uphold an image of British imperial power in Burma.

He heard reports of an elephant that had broken free of its chains and become aggressive, destroying a hut, killing a cow, and raiding fruit stalls. So he made arrangements for his rifle to arrive promptly at its location in order to deal with this potentially dangerous animal.

Legally, it was his duty.

Orwell had no choice but to shoot the elephant as it was destroying property and had killed one person, which caused much harm and distress for both parties involved. Yet Orwell felt immense guilt for shooting it because there could have been more peaceful solutions available; also, due to public pressure, he believed he had to shoot as he didn’t want to appear weak in front of everyone present.

Orwell knew he would be accused of cowardice if he did not shoot the animal, yet he did not want to face an angry crowd with shame. At first, he waited quietly in the shadows to observe how the elephant responded, but soon enough, it began attacking people, leaving Orwell terrified that it might trample him and start cheering for its destruction – or accuse him of racism, which might get him fired from work altogether.

So, he decided to kill the elephant to avoid appearing like a coward in front of the crowd. Orwell shot multiple shots into it until eventually it stopped attacking people; Orwell then felt guilty that killing it for personal pride had been at the expense of their lives.

The shooting of an elephant illuminates numerous critical aspects of colonialism. First, it highlights its unequal distribution of power: outsiders often exert undue influence over local populations in colonialism’s early years; this seems counterintuitive but remains part and parcel of colonial rule.

Orwell’s situation exemplified this imbalance of power perfectly. As a police officer, he was required to kill an elephant due to his duties and responsibilities as a colonial official – its destruction posed a direct threat to those living nearby and endangered their safety.

Orwell was overwhelmed by his duties and by the people’s intense dislike for him; many disliked his European background and decision to kill the elephant, not only by those fighting against British influence but by everyone in general. This hatred extended even beyond the borders of England itself.

Morally, it was his duty.

George Orwell is best known for writing the classic science fiction novel 1984 and political satire Animal Farm, but also wrote short works such as his essay “Shooting an Elephant”. In it, Orwell recalls a situation where he must decide whether or not to shoot a destructive elephant that had killed someone and caused damage in a village. Furthermore, according to Orwell, it was part of their responsibility as owners to watch over it, leading him to ultimately decide that killing was his duty as the owner of that elephant.

Orwell employs various rhetorical strategies in his essay to convince his audience. First, he attempts to establish his relationship with the people of Moulmein by writing that locals held an animus toward him: they would shout abuse and jeer at him when passing by.” This example of pathos makes the story more compelling.

Orwell utilizes anecdotes and first-person writing in his essay to increase relatability, while choosing first person gives the piece more credibility and gives a sense of authenticity, humanizing it further and lending it greater credibility – making Orwell’s narrative even more credible as it draws upon his personal experiences; another instance of ethos.

As a police officer for the British Empire, Orwell had to follow orders given to him by them. While feeling disconnected from Burmese people and dissatisfied with his job as a British colonial official, Orwell believed the British were corrupting Burma but carried out his duty despite this feeling of alienation from Burma itself. By shooting an elephant, however, Orwell showed signs that he was becoming disenchanted with imperialism and its beliefs.

Orwell’s essay stands in stark contrast to King’s “Letter from Birmingham Jail.” Whereas King’s letter underscored the difficulty of remaining neutral about social injustice, Orwell’s story showed how policemen can still perform their jobs while remaining impartial. Through telling this tale, Orwell hopes readers are inspired to get involved with their communities and fight injustice in their communities.

Socially, it was his duty.

George Orwell uses first-person perspective, metaphors, symbolism, irony, and connotative and denotative language to craft this essay into an effective work of literature. These tools immerse the audience into his experience as a colonial police officer while making them feel imperialism’s brutality firsthand. Furthermore, there are elements of pathos that add depth and make this work all the more compelling.

Orwell recognized that elephants were dangerous animals capable of maiming and even killing people and wanted to protect the Burmese people by killing them, but was concerned about what others thought if he didn’t do it. Orwell felt obliged to shoot the elephant since its threat represented a danger for which he was responsible; they considered shooting it an obligation to keep order among his people.

As Orwell requests his subordinate to fetch him the rifle, a large group of local Burmese people follows behind, eager to see an elephant killed and want Orwell to do it himself. Orwell understands he must comply with their desires if he intends to remain an enforcer for the British Empire and keep his job. In comparison, Orwell compares himself with an “empty, posing dummy” and the stereotypical figure of a sahib.

Orwell knew it would be wrong to kill the elephant, yet he was afraid of losing face in front of the crowd if he failed to kill it. Orwell shot from a distance, and it took nearly an hour for it to die; afterward, he felt guilty over what had transpired.

Orwell’s encounter with the elephant served as an eye-opener about imperialism, teaching him about its dangers. He understood how the British Empire forces oppression and degradation on those it colonized countries, not equalling up to them as people in power were controlling them. Orwell gained greater insight into imperialism from this encounter with an elephant, which later helped him write an essay on this subject matter.

Politically, it was his duty.

Orwell’s Tale of the Elephant illustrates his battle between peer pressure and morality. As a police officer, Orwell was expected to shoot it but didn’t want to, believing it had more worth alive than dead and fearing it might launch back into a rampage, which could be embarrassing for everyone involved. Still, though reluctant to kill it himself, yellow-skinned people expected him to shoot it, and eventually, this crowd pressure overwhelmed his moral convictions, leading him to shoot it three times before finally succumbing under the pressure of peer pressure to kill it all and kill it after it received three shots that killed it immediately.

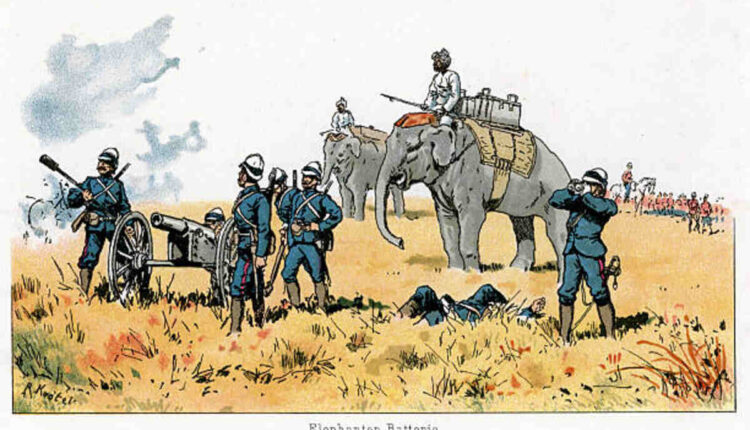

The elephant was tame but had entered its “must,” or male elephant’s period of extreme aggression that caused damage to lives and property. After breaking free of its chain in the night and breaking loose from its chains altogether, this elephant caused havoc; it destroyed somebody’s bamboo hut, killed a cow, raided fruit stalls, devoured their stock, etc.

Orwell must act quickly to protect his fellow villagers and himself, killing the elephant to prevent it from attacking more people and destroying the village. He had no other choice than to follow the law and kill this dangerous animal to ensure the safety of everyone.

Orwell eventually came to realize he had done the right thing and likened his service in the British Empire to the act of putting down a dangerous dog; when one attacks people or causes harm, its owner should act to remove it from society. Orwell found his rational principles clashing directly with his basic intuitions during this period, leading him down an unconventional path in his personal and professional life.

Orwell used an elephant as a symbol of British imperialism in Burma to demonstrate tensions between British colonists and their subjects; their struggle was between maintaining power while respecting local cultures; it took nearly half an hour for this scene to unfold because the animal struggled against being shot, reflecting hatred, mistrust, and resentment between British imperialists and Burmese subjects.